POSITHIVE TRIPS Text by Nicola Scevola

“Is it better to have cancer or AIDS?” Izabela Voieta, an infectologist at De Menezes hospital in the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais, often hears this kind of questions from panicking patients who have just discovered to be HIV positive. Her answer is always the same: “If treated properly, today you can lead a normal life with HIV virus”.

This is particularly true if you live in Brazil, where the local government has promoted an effective treatment program that helped containing the epidemic and reducing mortality. Today Brazil fares one the best model response to HIV/AIDS in the world, but the situation wasn’t always so good. In the early Nineties, incidence rates and estimates for future developments of the disease in the country were dramatic. And the prohibitive cost of AIDS medicaments meant that only few people could afford to be treated. But Brazil's national AIDS officials learned early on that they needed to work closely with civil society in order to successfully combat AIDS.

Activists clamoring for universal access to medicines were incorporated into the AIDS program and they convinced the government to commit to the free distribution of antiretroviral medications. In 1996 Brazil started distributing free ARV drugs to HIV positive patients. Since then, a major factor in Brazil’s success has been its ability to produce several AIDS drugs locally. In order to keep the cost down, the government also started overriding patents, taking advantage of the TRIPS agreement that allows developing countries to issue “compulsory licenses” for drugs when their governments deem it to be a public health emergency.

“The national treatment program has changed my life”, says 53 year-old Reinaldo de Brito Barreto, an HIV patient who lives in Recife. “Before I had to concentrate all my energy in finding money to buy ARV drugs. Now I can live my life at the fullest again”. Brazil response was based on both humanitarian and practical grounds. Access to health care as a human right is enshrined in the Brazilian Constitution and the government is essentially forced to do whatever it can to guarantee access to medicine and health care. HIV also increases risks of acquiring opportunistic infections and the cost for treating these infections, added to the social cost caused by inability or death, can be higher than the budget spent to treat HIV patients.

Free ARV distribution also helped Brazil in halving cases of mother-to-child transmission of the virus, guaranteeing people not only the right to life but also the right to procreate. But the government treatment program goes beyond medicament distribution. Social workers, psychologists and nutritionists assist patients and help them adhering to recommended ARV regimen, essential to their survival and quality of life. Specialized centers offer cosmetic treatment of HIV-related facial lipoatrophy that helps reducing stigma associated with the virus. “We even have an outpatients dedicated to transgender patients infected with HIV,” says Emi Shimma, spokeswoman for Reference and Training Center for Sexually Transmitted Diseases and AIDS (CRT) in Sao Paulo. “People come here from all Latin America because of the quality of the treatment”.

Brazil has also vigorously invested in prevention campaigns: in 2011, the government gave away 500 millions condoms for free, 38 times the number it distributed in 1994. This has contributed to a sharp decline of HIV/AIDS cases among high-risk categories. But while treatment programs have enjoyed overall success, the same cannot be said about prevention programs. In fact, recent data indicates condom use is declining. Only few years ago, the disease was widely debated and information was constantly made available to the public. But now HIV/AIDS-related issue have virtually disappeared from public debates and the media rarely mention this topic, despite the existence of a specialized news agency based in Sao Paulo that constantly offers news about HIV/AIDS to Brazilian outlets. In the long run, experts worry that this lack of attention could worsen incidence rates, tarnishing Brazil’s success story.

“Young people don’t perceive HIV as a mortal threat anymore and they tend not to bother with protections”, says Francisco Oliveira, infectologist at the Emilio Ribas hospital in Sao Paulo. “The same thing happens with senior citizens who were not used to use condoms when they were sexually active, and are now seeing a resurgence of sexual appetite thanks to new drugs like Viagra”.

STORIES

POSITHIVE STORIES: PERSPECTIVES

Pedro – retired army pilot, Sao Paulo

Pedro, 50, is gay and he’s been HIV+ since 1990. When he was infected he was working

as a helicopter pilot for the Brazilian army. This happened only few months before the

approval of a law that forbids HIV+ military pilots to fly, because of the possible damages

to their sight caused by the use of anti-retroviral medications. At the time, no one in the

army knew about Pedro’s health condition and in order to protect himself he decided to

voluntarily stop flying helicopters before he had to take the HIV test. He was transferred

to Sao Paulo and retired few years later. “The Brazilian system to treat AIDS works very

well,” he says. “I have foreigner friends who come to Brazil for this reason. The

government provides me free access to any sort of physician and treatment. If you are

retired and HIV+, like me, you don’t have to pay taxes on your income and the City of Sao

Paulo even gives you a free public transport card”. Prevention though seems to be less

efficient. “Lately I met many young kids who don’t want to use a condom,” he says. “And

when I tell them I am HIV+ they insist on having unprotected sex or just walk away”.

Severinho Raimundo - Correia Picanço Hospital, Recife

Raimundo is a 38-year-old truck driver. Lately his health worsened very quickly, he lost

weight and felt extremely weak so he decided to go from the village where he lives, some

80km from Recife, to the nearest hospital. From there he was transferred to the intensivecare

unit of the Correia Picanço Hospital in Recife, where he’s been treated for the last

three weeks. Shortly after being admitted to the hospital, he found out to be HIV+,

something he had never even considered. He refers to himself as a regular condom user

but, given his very weak immune system, doctors think he might have been positive for a

number of years. Unfortunately his wife turned out to be HIV+ as well.

Carlos Starling - Sociedade Mineira de Infectologia, Belo Horizonte

Starling is a well known Brazilian epidemiologist and infectologist. He’s vice-president of

the Sociedade Mineira de Infectologia and Scientific Coordinator of the Sociedade

Brasileira de Infectologia. At the beginning of his career he worked in Germany, where he

had the opportunity to treat his first HIV+ patients. In the mid-80s he moved back to

Brazil, just in time to witness the rapid spread of the epidemic. He still remembers the first

HIV+ patient he treated in Minas Gerais, a waiter who had just come back from New York

City. “Other doctors wouldn’t know what to do, they were too scared of being infected,”

he says. Since then he has treated thousands of patients suffering from HIV and AIDS.

"The clinical situation has improved significantly since the Brazilian government has

started to provide free access to anti-retroviral medicines," he points out. "This has not

only given back to patients their right to life but also their right to procreation. If treated

properly, today a HIV+ mother can give birth to a healthy child".

Reinaldo de Brito Barreto - Correia Picanço Hospital, Recife

Barreto is 53, works for a non-governmental organization and has known to be HIV+

since the 15th of March 1985, the day he was tested for the very first time. He contracted

the virus through an infected blood transfusion that, along with HIV, gave him hepatitis C

and syphilis. At the time, he says, artists and musicians in Rio de Janeiro would sell their

artworks to collect money and buy medicines to treat HIV+ patients. Money, though, was

never enough so they were forced to choose through raffles those who would actually get

treated. He was one of the lucky ones. “I used to go back and forth between the hospital

and the morgue, just across the street. After some time the guards would recognize me

and ask me: are you still alive?”. Before he moved to Recife in 1995, he had lost 32 of his

friends. “When the government started its treatment programs my life changed – I felt I

could make project for the future again and started to come the clinic and its gym”.

Physical exercise is useful to contrast AIDS-related muscular dystrophy, improves sleep

and it also helps increasing patients’ self-esteem.

Silvia Almeida - Anglo American Corp., Sao Paulo

Silvia is 48. She found out to be HIV+ back in 1994. It was her husband who gave her the

virus, without knowing. When they both found out to be positive, he only had a couple of

years to live. After he passed away she was left alone to fight her battle against the

disease and grow her two children, who were 14 and 4 years old. Luckily at the time

Almeida was working for Anglo-American, an international mining company active in

South Africa, which had standardized a protocol that allowed its HIV+ employees to be

adequately treated while working. Over the years, Silvia became the head of Anglo-

American Brazil’s HIV/AIDS program, which aims to raise awareness and support people

living with HIV. "I've always been very scrupulous in taking medications and I have never

had a single opportunistic infection," says Almeida. "Many people won’t believe me when

I tell them that I'm HIV+ because they associate the disease with an emaciated look. But

nowadays you don’t have to wear the disease on your face anymore. I feel fine to the

point that I need an alarm clock to remind me to take my medications!”

Izabela Voieta - Eduardo de Menezes Hospital, Belo Horizonte

Izabela, 35, is a physician specialized in the treatment of infectious and tropical diseases

and has been working for the past 8 years at the Eduardo de Menezes Hospital in Belo

Horizonte. There are some 70 patients in her unit, two thirds of which are normally

occupied by HIV+ patients. “It is still very common – she says – that patients are admitted

to the hospital without knowing they are HIV+. They assume they have some other

disease and then find out to be HIV+”. The first reaction is normally despair but “I try to

calm them down explaining that today HIV/AIDS is considered a chronic disease”. Minas

Gerais is a rather conservative State and there is still some stigma and discrimination

against people living with HIV. “The patients’ quality of life is much better now, with less

pills to take and simpler posology. But strict adherence to therapy remains critical for the

success of the treatment”.

Roseli Tardelli - Agencia de Noticias da AIDS, Sao Paulo

Tardelli is a journalist and the editor-in-chief of a news agency specialized in HIV/AIDS

that she founded ten years ago. The agency, the only one of its kind in the world, has its

roots in a tragedy that hit Tardelli personally. In 1989 her brother Sergio found out to be

HIV+ and began a legal battle against his medical insurance that refused to pay for his

treatment. When a court finally recognized his rights in 1993, it was too late for Sergio,

who died soon after, weighting only 30 kilos. After Sergio’s death, Tardelli kept writing

about HIV/AIDS and in 2003 she founded the Agencia de Noticias da AIDS, a non profit

organization that works to inform and keep the media engaged on this topic. “Back in the

90s you would hear a lot of talking about HIV and AIDS, while today the disease is almost

completely out of sight,” she points out. “But the necessity to inform people is still strong:

today the most affected by this epidemic are people under 25 and over 60, which also

represent the less informed segments of the population”.

Raul Quiroz – chief financial officer, Sao Paulo

Raul, 41, is the chief financial officer of a big financial institution in Brazil. He was born in

Mexico City and completed his studies in New York. After watching the movie

“Philadelphia” he felt compelled to help people dying of AIDS. He moved there and, as a

volunteer, learned many things about the disease. He then moved back to New York,

where he found out to be HIV+ in 2005. When his visa was about to expire, the bank he

was working for at the time offered him to sponsor a green card. But in order to become

a permanent resident, the US government forced you to take an HIV test. Since he didn’t

want to disclose his status he asked the bank to transfer him abroad. From then until

2010 – when the Obama administration lifted the ban for HIV+ people to enter the US – all

the times he went back to the States he had to hide his anti-retroviral medicines in boxes

of generic pills. “Brazil has great laws to help, support and treat HIV+ patients, even

foreigners like me. It was very important for me to be able to enroll in the Brazilian

National AIDS Program and benefit from the treatment. But the health system’s standards

are not the same everywhere and, besides the Centro de Referência e Treinamento where

I pick up my medications, I’d rather go to private clinics for my check-ups”.

INFOGRAPHICS Brazil - Care

The infographics are presented for informational purposes only. Every attempt has been made to ensure that the information contained herein is accurate. Figures and percentages are based on latest available data as collected by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and published on their respective websites.

THUMBNAILS AND CAPTIONS

A view of The Cristo Redentor from Santa Martaʼs Morro, in Rio de

Janeiro. In Brazil, the National Health System (NHS) - created with effect from the

promulgation of the new Federal Constitution in 1988 - made access to health a right of

the entire population and a duty of the State. Following these principles, as a response to

the AIDS epidemic, the Brazilian government has guaranteed universal and free of cost

access to ART since 1996.

A view of The Cristo Redentor from Santa Martaʼs Morro, in Rio de

Janeiro. In Brazil, the National Health System (NHS) - created with effect from the

promulgation of the new Federal Constitution in 1988 - made access to health a right of

the entire population and a duty of the State. Following these principles, as a response to

the AIDS epidemic, the Brazilian government has guaranteed universal and free of cost

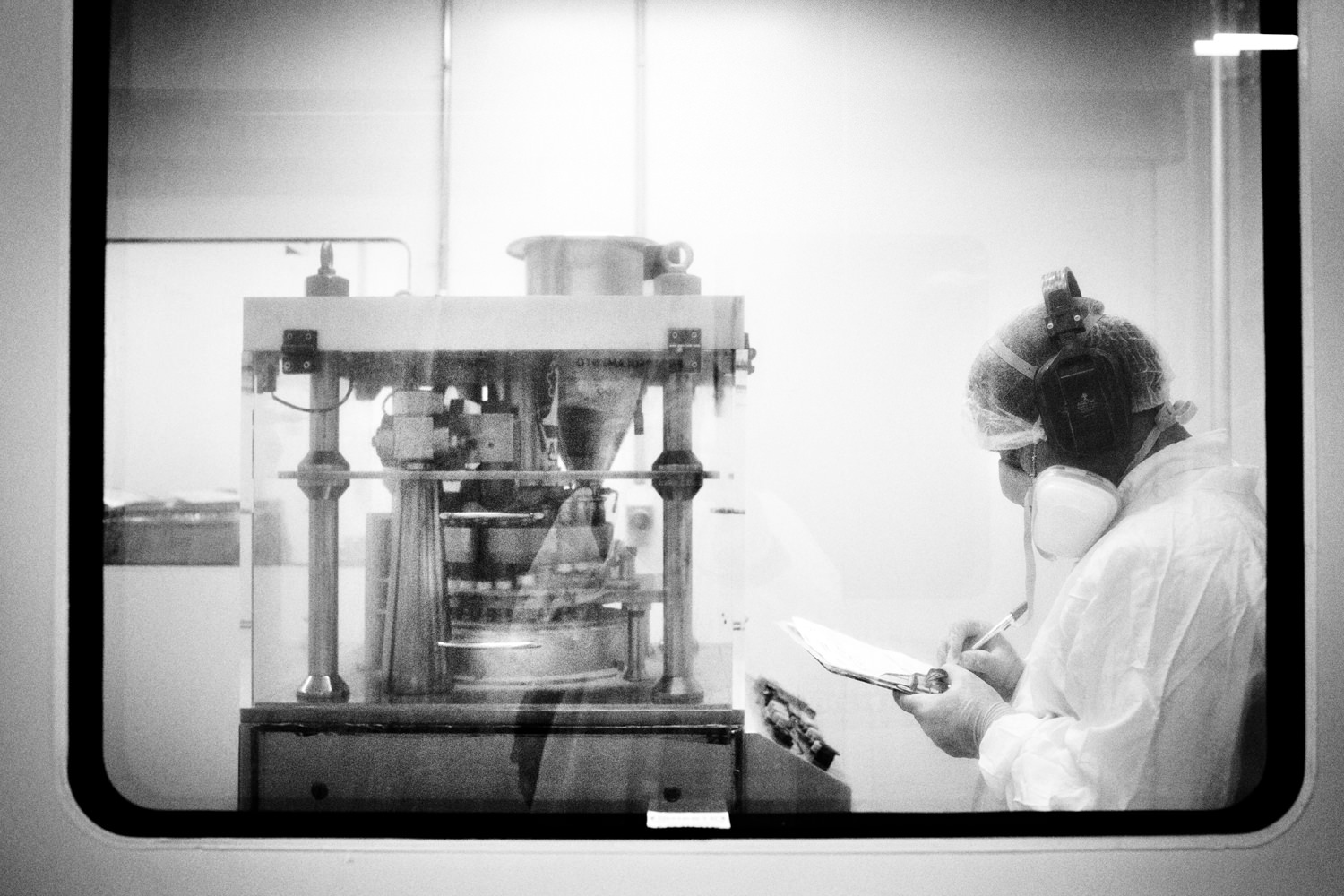

access to ART since 1996. A LAFEPE employee is working at the machine that mixes raw

materials and excipients to produce ARV tablets. LAFEPE was the first official laboratory

in Brazil to produce, back in 1994, the antiretroviral zidovudine (AZT). After years of

research and in partnership with universities and other laboratories, it developed

efavirenz, a fixed dose combination of ARV that is part of the HIV treatment. Today there

are ten different ARV medicines produced by public and private laboratories for the

government’s Sistema Unico de Saude.

A LAFEPE employee is working at the machine that mixes raw

materials and excipients to produce ARV tablets. LAFEPE was the first official laboratory

in Brazil to produce, back in 1994, the antiretroviral zidovudine (AZT). After years of

research and in partnership with universities and other laboratories, it developed

efavirenz, a fixed dose combination of ARV that is part of the HIV treatment. Today there

are ten different ARV medicines produced by public and private laboratories for the

government’s Sistema Unico de Saude. Oscar Niemeyerʼs Contemporary Art Museum in Niterói faces Rio de

Janeiroʼs Guanabara Bay. Niemeyer's designs are very much contemporary and

somehow still daring: mixing innovation and courage, freedom and invention they could

easily represent the efforts done by the Brazilian governments to successfully address the

HIV/AIDS epidemic during the last three decades.

Oscar Niemeyerʼs Contemporary Art Museum in Niterói faces Rio de

Janeiroʼs Guanabara Bay. Niemeyer's designs are very much contemporary and

somehow still daring: mixing innovation and courage, freedom and invention they could

easily represent the efforts done by the Brazilian governments to successfully address the

HIV/AIDS epidemic during the last three decades. A terminally ill patient is taken care of by a nurse at the Emilio Ribas

Institute of Infectious Diseases in Sao Paulo. The Emilio Ribas Institute of Infectious

Diseases has 200 beds distributed in seven inpatient units, including a pediatric intensive

care unit. Some 70% of the patients admitted in these units and 90% of those attended

at the emergency rooms of the hospital are people living with HIV/AIDS. Founded in 1880,

Emilio Ribas is responsible for more than 45% of beds for AIDS patients in São Paulo and

currently serves more than 30,000 patients per year.

A terminally ill patient is taken care of by a nurse at the Emilio Ribas

Institute of Infectious Diseases in Sao Paulo. The Emilio Ribas Institute of Infectious

Diseases has 200 beds distributed in seven inpatient units, including a pediatric intensive

care unit. Some 70% of the patients admitted in these units and 90% of those attended

at the emergency rooms of the hospital are people living with HIV/AIDS. Founded in 1880,

Emilio Ribas is responsible for more than 45% of beds for AIDS patients in São Paulo and

currently serves more than 30,000 patients per year. Pharmaceutical machinery at Ezequiel Dias Foundation (FUNED), the

official laboratory in Minas Gerais State. FUNED produces nevirapine and a cocktail of

zidovudine and lamividuna. Recently the lab also started the production of tenofovir,

which is considered by the Ministry of Health an item of public interest and strategic for

the public health system. Today there are ten different ARV medicines produced by

public and private laboratories for the government’s Sistema Unico de Saude.

Pharmaceutical machinery at Ezequiel Dias Foundation (FUNED), the

official laboratory in Minas Gerais State. FUNED produces nevirapine and a cocktail of

zidovudine and lamividuna. Recently the lab also started the production of tenofovir,

which is considered by the Ministry of Health an item of public interest and strategic for

the public health system. Today there are ten different ARV medicines produced by

public and private laboratories for the government’s Sistema Unico de Saude. Doctor Mario Warde - head of the National Program for Treatment of

patients with lipodystrophy and one of the few plastic surgeons who raised the issue of

the need for a public treatment for facial lipodystrophy - shows a pack of

polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) syringes used for soft tissues augmentation. Reparative

surgery is provided for free by the Brazilian government and is meant to enhance HIV+

people self-image and self-esteem and to reduce prejudice, discrimination and other

negative social behaviors against HIV+ people.

Doctor Mario Warde - head of the National Program for Treatment of

patients with lipodystrophy and one of the few plastic surgeons who raised the issue of

the need for a public treatment for facial lipodystrophy - shows a pack of

polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) syringes used for soft tissues augmentation. Reparative

surgery is provided for free by the Brazilian government and is meant to enhance HIV+

people self-image and self-esteem and to reduce prejudice, discrimination and other

negative social behaviors against HIV+ people. Pharmaceutical machinery at LAFEPE, the first official laboratory in

Brazil to produce, back in 1994, the antiretroviral zidovudine (AZT). After years of research

and in partnership with universities and other laboratories, LAFEPE developed efavirenz,

a fixed dose combination of ARV that is part of the HIV treatment. Today there are ten

different ARV medicines produced by public and private laboratories for the government’s

Sistema Unico de Saude.

Pharmaceutical machinery at LAFEPE, the first official laboratory in

Brazil to produce, back in 1994, the antiretroviral zidovudine (AZT). After years of research

and in partnership with universities and other laboratories, LAFEPE developed efavirenz,

a fixed dose combination of ARV that is part of the HIV treatment. Today there are ten

different ARV medicines produced by public and private laboratories for the government’s

Sistema Unico de Saude. Doctors at work in the laboratories of the Reference and Training

Center for Sexually Transmitted Diseases and AIDS (CRT) in Sao Paulo. The ARV

medicines produced by the public laboratories for the government’s Sistema Unico de

Saude are conveyed to the reference centers for free distribution to people living with HIV

and AIDS. CRTʼs mission is to reduce the vulnerability of the population of São Paulo in

acquiring STDs and HIV/AIDS.

Doctors at work in the laboratories of the Reference and Training

Center for Sexually Transmitted Diseases and AIDS (CRT) in Sao Paulo. The ARV

medicines produced by the public laboratories for the government’s Sistema Unico de

Saude are conveyed to the reference centers for free distribution to people living with HIV

and AIDS. CRTʼs mission is to reduce the vulnerability of the population of São Paulo in

acquiring STDs and HIV/AIDS. Renato, a 27 years old hair stylist, was first hospitalized at Correia

Picanço, the reference hospital for HIV/AIDS in Pernambuco State, because he had TBC

symptoms. Then, three years ago, he found out to be also HIV+. He had suspected to be

HIV+ but never took the test because he was scared to know about his status. The

estimated total ART coverage of HIV+ people in need has increased from 71% in 2011 to

87% in 2012.

Renato, a 27 years old hair stylist, was first hospitalized at Correia

Picanço, the reference hospital for HIV/AIDS in Pernambuco State, because he had TBC

symptoms. Then, three years ago, he found out to be also HIV+. He had suspected to be

HIV+ but never took the test because he was scared to know about his status. The

estimated total ART coverage of HIV+ people in need has increased from 71% in 2011 to

87% in 2012. Pharmaceutical machinery at Ezequiel Dias Foundation (FUNED), the

official laboratory in Minas Gerais State. FUNED produces nevirapine and a cocktail of

zidovudine and lamividuna. Recently the lab also started the production of tenofovir,

which is considered by the Ministry of Health an item of public interest and strategic for

the public health system. Today there are ten different ARV medicines produced by

public and private laboratories for the government’s Sistema Unico de Saude.

Pharmaceutical machinery at Ezequiel Dias Foundation (FUNED), the

official laboratory in Minas Gerais State. FUNED produces nevirapine and a cocktail of

zidovudine and lamividuna. Recently the lab also started the production of tenofovir,

which is considered by the Ministry of Health an item of public interest and strategic for

the public health system. Today there are ten different ARV medicines produced by

public and private laboratories for the government’s Sistema Unico de Saude. Severinho Raimundo, 38, is a truck driver who’s been hospitalized in

the Intensive Care Unit at Correia Picanço, the reference hospital for HIV/AIDS in

Pernambuco State, because his health was deteriorating very quickly. Just a couple of

weeks before this picture was taken he found out to be HIV positive even though, given

his very bad conditions, doctors presume he’s been HIV positive at least for the last 5 to

10 years. The estimated total ART coverage of HIV+ people in need has increased from

71% in 2011 to 87% in 2012.

Severinho Raimundo, 38, is a truck driver who’s been hospitalized in

the Intensive Care Unit at Correia Picanço, the reference hospital for HIV/AIDS in

Pernambuco State, because his health was deteriorating very quickly. Just a couple of

weeks before this picture was taken he found out to be HIV positive even though, given

his very bad conditions, doctors presume he’s been HIV positive at least for the last 5 to

10 years. The estimated total ART coverage of HIV+ people in need has increased from

71% in 2011 to 87% in 2012. Rio de Janeiroʼs Guanabara Bay seen form Oscar Niemeyerʼs

Contemporary Art Museum in Niterói. Niemeyer's designs are very much contemporary

and somehow still daring: mixing innovation and courage, freedom and invention they

could easily represent the efforts done by the Brazilian governments to successfully

address the HIV/AIDS epidemic during the last three decades.

Rio de Janeiroʼs Guanabara Bay seen form Oscar Niemeyerʼs

Contemporary Art Museum in Niterói. Niemeyer's designs are very much contemporary

and somehow still daring: mixing innovation and courage, freedom and invention they

could easily represent the efforts done by the Brazilian governments to successfully

address the HIV/AIDS epidemic during the last three decades. Juliane Soares do Santos, 19, was hospitalized at Edoardo de

Menezes, the reference hospital for HIV/AIDS in Minas Gerais State, because of a

suspect case of TBC. An alcohol and drug abuser, she already knew to be HIV positive

but didn’t adhere to the treatment because of her dependence on drugs. In 2009, only

54,31% of IDUs reported the use of sterile syringes and a poor 15% received a HIV test

in the last 12 months.

Juliane Soares do Santos, 19, was hospitalized at Edoardo de

Menezes, the reference hospital for HIV/AIDS in Minas Gerais State, because of a

suspect case of TBC. An alcohol and drug abuser, she already knew to be HIV positive

but didn’t adhere to the treatment because of her dependence on drugs. In 2009, only

54,31% of IDUs reported the use of sterile syringes and a poor 15% received a HIV test

in the last 12 months. Avenida Paulista in Sao Paulo is the financial and commercial heart of

the capital of the homonymous state. The first cases of HIV in Brazil were reported in Sao

Paulo in 1982 while in 1985, the same year that democracy was restored in the country,

the government set up the first National AIDS Program in partnership with civil society

groups. In 2010 Brazil spent 70,2% – some 930 millions of dollars – of its HIV/AIDS

budget in Care and Treatments programs.

Avenida Paulista in Sao Paulo is the financial and commercial heart of

the capital of the homonymous state. The first cases of HIV in Brazil were reported in Sao

Paulo in 1982 while in 1985, the same year that democracy was restored in the country,

the government set up the first National AIDS Program in partnership with civil society

groups. In 2010 Brazil spent 70,2% – some 930 millions of dollars – of its HIV/AIDS

budget in Care and Treatments programs. A LAFEPE employee is packing up boxes of tablets that will be sent

to the reference centers for free distribution of ARV to people living with HIV/AIDS.

LAFEPE was the first official laboratory in Brazil to produce, back in 1994, the

antiretroviral zidovudine (AZT). After years of research and in partnership with universities

and other laboratories, it developed efavirenz, a fixed dose combination of ARV that is

part of the HIV treatment. Today there are ten different ARV medicines produced by

public and private laboratories for the government’s Sistema Unico de Saude.

A LAFEPE employee is packing up boxes of tablets that will be sent

to the reference centers for free distribution of ARV to people living with HIV/AIDS.

LAFEPE was the first official laboratory in Brazil to produce, back in 1994, the

antiretroviral zidovudine (AZT). After years of research and in partnership with universities

and other laboratories, it developed efavirenz, a fixed dose combination of ARV that is

part of the HIV treatment. Today there are ten different ARV medicines produced by

public and private laboratories for the government’s Sistema Unico de Saude. An older HIV+ patient is being cured at the Hospital Edoardo de

Menezes, the reference center for HIV/AIDS in Minas Gerais State. With the onset of the

AIDS epidemic, in the 80s the H.E.M opened the first beds for patients with the disease

and soon after became a reference for the treatment of HIV and ADIS. Currently the

hospital is also working in research and professional training and its outpatient clinic

plays an important role as part of the ministerial Care and Treatment Programs.

An older HIV+ patient is being cured at the Hospital Edoardo de

Menezes, the reference center for HIV/AIDS in Minas Gerais State. With the onset of the

AIDS epidemic, in the 80s the H.E.M opened the first beds for patients with the disease

and soon after became a reference for the treatment of HIV and ADIS. Currently the

hospital is also working in research and professional training and its outpatient clinic

plays an important role as part of the ministerial Care and Treatment Programs. The Emilio Ribas Institute of Infectious Diseases has 200 beds

distributed in seven inpatient units, including a pediatric intensive care unit. Some 70% of

the patients admitted in these units and 90% of those attended at the emergency rooms

of the hospital are people living with HIV/AIDS. Founded in 1880, Emilio Ribas is

responsible for more than 45% of beds for AIDS patients in São Paulo and currently

serves more than 30,000 patients per year.

The Emilio Ribas Institute of Infectious Diseases has 200 beds

distributed in seven inpatient units, including a pediatric intensive care unit. Some 70% of

the patients admitted in these units and 90% of those attended at the emergency rooms

of the hospital are people living with HIV/AIDS. Founded in 1880, Emilio Ribas is

responsible for more than 45% of beds for AIDS patients in São Paulo and currently

serves more than 30,000 patients per year. The pharmacy at the Hospital Edoardo de Menezes, the reference

center for HIV/AIDS in Minas Gerais State. With the onset of the AIDS epidemic, in the

80s the H.E.M opened the first beds for patients with the disease and soon after became

a reference for the treatment of HIV and ADIS. Currently the hospital is also working in

research and professional training and its outpatient clinic plays an important role as part

of the ministerial Care and Treatment Programs.

The pharmacy at the Hospital Edoardo de Menezes, the reference

center for HIV/AIDS in Minas Gerais State. With the onset of the AIDS epidemic, in the

80s the H.E.M opened the first beds for patients with the disease and soon after became

a reference for the treatment of HIV and ADIS. Currently the hospital is also working in

research and professional training and its outpatient clinic plays an important role as part

of the ministerial Care and Treatment Programs. Young men are playing soccer on the beach of Ipanema, in Rio de

Janeiro. In Brazil, the National Health System (NHS) - created with effect from the

promulgation of the new Federal Constitution in 1988 - made access to health a right of

the entire population and a duty of the State. Following these principles, as a response to

the AIDS epidemic, the Brazilian government has guaranteed universal and free of cost

access to ART since 1996.

Young men are playing soccer on the beach of Ipanema, in Rio de

Janeiro. In Brazil, the National Health System (NHS) - created with effect from the

promulgation of the new Federal Constitution in 1988 - made access to health a right of

the entire population and a duty of the State. Following these principles, as a response to

the AIDS epidemic, the Brazilian government has guaranteed universal and free of cost

access to ART since 1996. Maria de Socorrro, 42, was first diagnosed with meningitis and only

after she found out to be also HIV positive. She is now hospitalized at Correia Picanço,

the reference hospital for HIV/AIDS in Pernambuco State. She has contracted HIV from

her former husband who has then died of AIDS-related causes. In Brazil there is an

estimated 380,000 people in need of ART. The latest available data show that some 48%

of HIV+ people on ARV treatment follow the regimen recommended as the first treatment

option by the Brazilian Treatment Recommendations and that 73,4% of them are still on

treatment after 60 months.

Maria de Socorrro, 42, was first diagnosed with meningitis and only

after she found out to be also HIV positive. She is now hospitalized at Correia Picanço,

the reference hospital for HIV/AIDS in Pernambuco State. She has contracted HIV from

her former husband who has then died of AIDS-related causes. In Brazil there is an

estimated 380,000 people in need of ART. The latest available data show that some 48%

of HIV+ people on ARV treatment follow the regimen recommended as the first treatment

option by the Brazilian Treatment Recommendations and that 73,4% of them are still on

treatment after 60 months. Avenida Paulista in Sao Paulo is the financial and commercial heart of

the capital of the homonymous state. The first cases of HIV in Brazil were reported in Sao

Paulo in 1982 while in 1985, the same year that democracy was restored in the country,

the government set up the first National AIDS Program in partnership with civil society

groups. In 2010 Brazil spent 70,2% – some 930 millions of dollars – of its HIV/AIDS

budget in Care and Treatments programs.

Avenida Paulista in Sao Paulo is the financial and commercial heart of

the capital of the homonymous state. The first cases of HIV in Brazil were reported in Sao

Paulo in 1982 while in 1985, the same year that democracy was restored in the country,

the government set up the first National AIDS Program in partnership with civil society

groups. In 2010 Brazil spent 70,2% – some 930 millions of dollars – of its HIV/AIDS

budget in Care and Treatments programs.